Often beneath the wave, wide from this ledge

The dice of drowned men's bones he saw bequeath

An embassy. Their numbers as he watched,

Beat on the dusty shore and were obscured.

And wrecks passed without sound of bells,

The calyx of death's bounty giving back

A scattered chapter, livid hieroglyph,

The portent wound in corridors of shells.

Then in the circuit calm of one vast coil,

Its lashings charmed and malice reconciled,

Frosted eyes there were that lifted altars;

And silent answers crept across the stars.

Compass, quadrant and sextant contrive

No farther tides . . . High in the azure steeps

Monody shall not wake the mariner.

This fabulous shadow only the sea keeps.

Editor: Zireaux

A risk, I know, to post this poem by Crane. I can already hear the twitter-twatter of distracted brains, like bird feet on a tin roof. The furrow of brows(ers). The clicks of the mice -- back-button, window closed. What a strain this cranial Crane! Too hard, too dense!

But stay, my reader. Let us creep across the stars. A little voyage for us to make. A little ship for us to sink in.

It's in our biology, programmed in our souls, to feel attraction to water. Crane, who found his dirty pleasure (dirty to him, that is) in sailors and their scepters, leapt off a steamship into the Gulf of Mexico. A suicide, apparently, after a male crew member responded violently to his physical advances.

"Harold Hart Crane 1899–1932 lost at sea," reads the inscription on his father's tombstone.

I'm no Cranophile, not by a longboat, and only recently -- budded by Bloom (Harold) and carried by a Griffin (John) -- has my interest come anywhere near the poet. But here's Crane now, floating beside us, his debris on the page, in water writ, forever inscribed in "Melville's Tomb."

And it's not every day a dead man speaks. Poets know death. They betroth themselves to death and learn how to "charm its lashings," so to speak (see my notes on "Of Mere Being"). One measure of a great poet: The degree to which she mingles amongst the living and the dead.

In the history of great poetic voyages, Melville -- who was foremost a poet (a fact I've stated before and which so often astonishes my readers, as if there was any question about it) -- was death's first mate and closest companion. Our Harold Crane, by comparison, was a mere able seaman, and his poem "At Melville's Tomb" is a little wooden rower compared to Herman's mighty Pequod. A single swipe of Moby's tail would dash this poem into a 110 pieces.

But it holds water. It's seaworthy. Can survive a humpback, maybe. Keep us from the sharks.

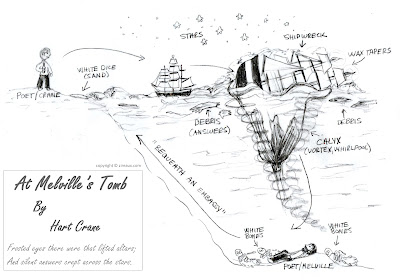

Observe my diagram. Most importantly, observe the position of the drowned Melville "beneath the waves" (he died and was buried on land, in fact, but Crane is speaking of his spirit here). Observe the living poet, standing on shore, beer bottle in hand, contemplating the ocean from his "ledge." Ledge, of course, being a thing from which people, especially edgy, ledgy poets, often fall...or leap.

We start with the "embassy" -- a Shakespearean locution for a message (see "Sonnet XLV," Twelfth Night, King Henry V, etc) -- which is "bequeathed" from sea to land, from washed-up bones to (dust-to) dusty sand. Speaking of messages, are those Crane's fingerprints on chapter 104 of Moby Dick from where he stole the word "bequeath" -- indeed stole the whole idea of messages coming from the mysterious underwater dead?

They are. The word "bequeath" appears once is that leviathan novel, in the chapter titled, suitably, "The Fossile Whale." Ishmael describes how whales "bequeath [their] ancient bust" in limestone and marl. Messages from bones. And interestingly, in the very next sentence, Ishmael describes how whales also appeared in Egyptian hieroglyphics -- writing, forsooth! -- represented by the print of a whale's fluke.

You can see, in my diagram, this cycle from bones to messages to chapters and hieroglyphs -- and this is very important, because Crane is about to deliver his most astonishing and brilliant couplet:

Frosted eyes there were that lifted altars;

And silent answers crept across the stars.

Crane himself offered clues about these lines in a letter to the perplexed editor of Poetry magazine, Harriet Monroe, who initially rejected the poem. But Crane assumes -- incorrectly -- his readers can at least understand the basic layout of his vision.

I've read at least a dozen other commentators of these lines. Bloom, Buckingham, Franks, Irwin, Leibowitz, Lewis, Penn Warren, Quinn, Tate, Woods, others. Crane's metaphors are so tightly packed (the calyx, for example, possesses both the whirlpool-like cavity created by a sinking ship and the flowers one puts on a grave) that none of these admirers seem to completely grasp the clear visual precision, the exactitude, which Crane has achieved.

Monroe couldn't understand how eyes could "lift altars." But in chapter 119 of Moby Dick, titled "The Candles," Melville writes of the corpusants (also known as St. Elmos Fire) that ignite the Pequods masts: "Each of the three tall masts was silently burning in that sulphurous air, like three gigantic wax tapers before an altar." The sky, the horizon in Moby Dick, is a kind of altar, the masts are like candles. To Crane's drowning sailors then, their frosted eyes looking upward as they sink into the ocean depths, it really would appear as if the alter were being lifted.

And what about the answers creeping across the stars? "As soon as the water has closed over a ship," Crane writes in his polite exegesis to Monroe, "this whirlpool sends up broken spars, wreckage, etc., which can be alluded to as livid hieroglyphs, making a scattered chapter..."

In other words, the "embassy," or message, has gone out to the shore; its "answer" then -- following the allure of the sea -- has come back by ship, which (like Ahab's Pequod) founders and sinks, leaving its wreckage, as scattered chapters, or livid (sea-smeared) hieroglyphs, to float across the ocean's surface.

Observe again my diagram and see my point: From Melville's perspective, from his position at the cruel bottom of the ocean looking upward from his tomb, the "answers," the replies to the "embassy," the scattered bits of wreckage, really would appear to silently creep across the stars.

The silence here is crucial, too. We can hear so little when we're underwater. Especially at the bottom of the sea. Wrecks pass "without sound of bells" -- the same bells which Crane borrows from chapter nine of Moby Dick: "The continual tolling of a bell in a ship that is foundering at sea in a fog".

Similarly the floating wreckage above us is absolutely silent. This will hurt Crane-lovers, but Disney -- a la Pirates of the Caribbean -- has given this perspective an almost camp quality; camera looking up from below at the floating bodies and debris above. And, too, the dead silence.

So naturally the "monody" -- the song of poets, of this poet, this poem, coming as it does above the boundaries of Melville's tomb, "high in the azure steeps" (the word "steeps" packed not just with height and loftiness, but with eyes, jewels, stars) -- is silent as well. With this understanding, with this sense of being deep underwater, amidst the absolute silence, the final line of the poem presents itself as -- ironically, given Crane's craving to leap from the ledge -- a celebration of being alive.

Because to the sea-entombed Melville, to "the mariner" looking up from below, the water's surface is the limit of his world. There are "no farther tides." Life, music, poetry, beauty, the sheer power of Crane's language, this fabulous world in which we live above the surface of the sea -- it's but a shadow to those who lie beneath.

-----------

Zireaux, who can't help but break a word-limit for Herman and Hart, is the author of four novels, including Kamal, which is currently being serialized on the web. His first novel, written in 1990s, will be available in paperback soon (with a free copy going to whoever solves this puzzle poem).

Please be sure to visit the poets listed in the sidebar. Surely there's a Hart amongst them -- Crane and Melville both sharing periods in their careers of extreme, debilitating under-appreciation. It's a good reader's responsibility, therefore, to locate and cherish the treasures in the tolling fog.

The dice of drowned men's bones he saw bequeath

An embassy. Their numbers as he watched,

Beat on the dusty shore and were obscured.

And wrecks passed without sound of bells,

The calyx of death's bounty giving back

A scattered chapter, livid hieroglyph,

The portent wound in corridors of shells.

Then in the circuit calm of one vast coil,

Its lashings charmed and malice reconciled,

Frosted eyes there were that lifted altars;

And silent answers crept across the stars.

Compass, quadrant and sextant contrive

No farther tides . . . High in the azure steeps

Monody shall not wake the mariner.

This fabulous shadow only the sea keeps.

|

| Zireaux's diagram of "At Melville's Tomb" (click to expand). Special thanks to Lynda Farrington Wilson for her help with the drawing. |

A risk, I know, to post this poem by Crane. I can already hear the twitter-twatter of distracted brains, like bird feet on a tin roof. The furrow of brows(ers). The clicks of the mice -- back-button, window closed. What a strain this cranial Crane! Too hard, too dense!

But stay, my reader. Let us creep across the stars. A little voyage for us to make. A little ship for us to sink in.

It's in our biology, programmed in our souls, to feel attraction to water. Crane, who found his dirty pleasure (dirty to him, that is) in sailors and their scepters, leapt off a steamship into the Gulf of Mexico. A suicide, apparently, after a male crew member responded violently to his physical advances.

"Harold Hart Crane 1899–1932 lost at sea," reads the inscription on his father's tombstone.

I'm no Cranophile, not by a longboat, and only recently -- budded by Bloom (Harold) and carried by a Griffin (John) -- has my interest come anywhere near the poet. But here's Crane now, floating beside us, his debris on the page, in water writ, forever inscribed in "Melville's Tomb."

And it's not every day a dead man speaks. Poets know death. They betroth themselves to death and learn how to "charm its lashings," so to speak (see my notes on "Of Mere Being"). One measure of a great poet: The degree to which she mingles amongst the living and the dead.

In the history of great poetic voyages, Melville -- who was foremost a poet (a fact I've stated before and which so often astonishes my readers, as if there was any question about it) -- was death's first mate and closest companion. Our Harold Crane, by comparison, was a mere able seaman, and his poem "At Melville's Tomb" is a little wooden rower compared to Herman's mighty Pequod. A single swipe of Moby's tail would dash this poem into a 110 pieces.

But it holds water. It's seaworthy. Can survive a humpback, maybe. Keep us from the sharks.

Observe my diagram. Most importantly, observe the position of the drowned Melville "beneath the waves" (he died and was buried on land, in fact, but Crane is speaking of his spirit here). Observe the living poet, standing on shore, beer bottle in hand, contemplating the ocean from his "ledge." Ledge, of course, being a thing from which people, especially edgy, ledgy poets, often fall...or leap.

We start with the "embassy" -- a Shakespearean locution for a message (see "Sonnet XLV," Twelfth Night, King Henry V, etc) -- which is "bequeathed" from sea to land, from washed-up bones to (dust-to) dusty sand. Speaking of messages, are those Crane's fingerprints on chapter 104 of Moby Dick from where he stole the word "bequeath" -- indeed stole the whole idea of messages coming from the mysterious underwater dead?

They are. The word "bequeath" appears once is that leviathan novel, in the chapter titled, suitably, "The Fossile Whale." Ishmael describes how whales "bequeath [their] ancient bust" in limestone and marl. Messages from bones. And interestingly, in the very next sentence, Ishmael describes how whales also appeared in Egyptian hieroglyphics -- writing, forsooth! -- represented by the print of a whale's fluke.

You can see, in my diagram, this cycle from bones to messages to chapters and hieroglyphs -- and this is very important, because Crane is about to deliver his most astonishing and brilliant couplet:

Frosted eyes there were that lifted altars;

And silent answers crept across the stars.

Crane himself offered clues about these lines in a letter to the perplexed editor of Poetry magazine, Harriet Monroe, who initially rejected the poem. But Crane assumes -- incorrectly -- his readers can at least understand the basic layout of his vision.

I've read at least a dozen other commentators of these lines. Bloom, Buckingham, Franks, Irwin, Leibowitz, Lewis, Penn Warren, Quinn, Tate, Woods, others. Crane's metaphors are so tightly packed (the calyx, for example, possesses both the whirlpool-like cavity created by a sinking ship and the flowers one puts on a grave) that none of these admirers seem to completely grasp the clear visual precision, the exactitude, which Crane has achieved.

|

| Looking up from below: Hart Crane would have appreciated this camera angle in the movie Life of Pi. |

And what about the answers creeping across the stars? "As soon as the water has closed over a ship," Crane writes in his polite exegesis to Monroe, "this whirlpool sends up broken spars, wreckage, etc., which can be alluded to as livid hieroglyphs, making a scattered chapter..."

In other words, the "embassy," or message, has gone out to the shore; its "answer" then -- following the allure of the sea -- has come back by ship, which (like Ahab's Pequod) founders and sinks, leaving its wreckage, as scattered chapters, or livid (sea-smeared) hieroglyphs, to float across the ocean's surface.

Observe again my diagram and see my point: From Melville's perspective, from his position at the cruel bottom of the ocean looking upward from his tomb, the "answers," the replies to the "embassy," the scattered bits of wreckage, really would appear to silently creep across the stars.

The silence here is crucial, too. We can hear so little when we're underwater. Especially at the bottom of the sea. Wrecks pass "without sound of bells" -- the same bells which Crane borrows from chapter nine of Moby Dick: "The continual tolling of a bell in a ship that is foundering at sea in a fog".

Similarly the floating wreckage above us is absolutely silent. This will hurt Crane-lovers, but Disney -- a la Pirates of the Caribbean -- has given this perspective an almost camp quality; camera looking up from below at the floating bodies and debris above. And, too, the dead silence.

So naturally the "monody" -- the song of poets, of this poet, this poem, coming as it does above the boundaries of Melville's tomb, "high in the azure steeps" (the word "steeps" packed not just with height and loftiness, but with eyes, jewels, stars) -- is silent as well. With this understanding, with this sense of being deep underwater, amidst the absolute silence, the final line of the poem presents itself as -- ironically, given Crane's craving to leap from the ledge -- a celebration of being alive.

Because to the sea-entombed Melville, to "the mariner" looking up from below, the water's surface is the limit of his world. There are "no farther tides." Life, music, poetry, beauty, the sheer power of Crane's language, this fabulous world in which we live above the surface of the sea -- it's but a shadow to those who lie beneath.

-----------

Zireaux, who can't help but break a word-limit for Herman and Hart, is the author of four novels, including Kamal, which is currently being serialized on the web. His first novel, written in 1990s, will be available in paperback soon (with a free copy going to whoever solves this puzzle poem).

Please be sure to visit the poets listed in the sidebar. Surely there's a Hart amongst them -- Crane and Melville both sharing periods in their careers of extreme, debilitating under-appreciation. It's a good reader's responsibility, therefore, to locate and cherish the treasures in the tolling fog.

8 comments:

Thanks Zireaux for the unravelling. I was hooked in by Crane's language without necessarily understanding it. Your patient explication was equally fascinating.

Love it - even the bits I don't completely understand.

I love Crane. Funny enough, the poet I'm sharing this week, Phil Rice, has a lot to do with my appreciation of this poet.

Thanks very much for the poem and your engaging comments - love it all and love the challenge and the thought processes that follow. I especially like your "It's in our biology, programmed in our souls, to feel attraction to water."

A wondrous selection of poems this week. We can categorize them thus:

Melvillian Joyceterpieces...

Harvey Malloy's "Abandoned Car"

Shakespeare's "Sonnet XVIII"

Hart Craniun, T.S. Eliotrical...(lurking wolves in Jones and Moeller, shared soliduses -- solidi? -- in Ponder and Nelson).

Tim Jones's "Jump in the Fire"

Eileen Moeller's "Hermit in Winter"

Rethabile Masilo's "The Edge"

Bill Nelson's "all the love poems"

Alicia Ponder's "Census"

Robert Sullivan's "New Eclipse"

Little creatures, big ideas...(involving a pig, a snail and a cockroach)

Kevin Brophy's "Taking a Pig to Market"

Helen McKinlay's "Careless love"

Don Marquis's "The lesson of the moth"

Straight-talking lyricism, earnest love...

Andrew Bell's "The Unheralded"

William Stafford's "A Ritual to Read to Each Other"

Phil Rice's "The Mornings"

Helen Rickerby's "March 4 (work in progress)"

Apologies if I missed any. I'm partial to Malloy (he's sitting, after all, beside Shakespeare on the list!), and Don Marquis gets a mention, too, but every poem offered a unique glimpse of a unique beauty.

Will respond to the Crane comments soon. There's such a terrific chasm between Crane and the great poets such as Melville, Coleridge, Whitman, Shelley, Poe and so forth -- and I just want to make one last desperate attempt at trying to identify exactly what keeps Crane (and T.S. Eliot, Wallace Stevens, etc) so far from their company.

Please forgive my typos in the comment above. It's Molloy, of course, not Malloy. And "Cranium" not "Craniun".

Answer to your question soon, John.

I enjoyed "At Melville's Tomb", Zireaux--love the 'more is more' use of language.

To be alive is to be on the good ship Real

To be real is to speculate on what we see and feel

To watch the recombinant coding of the world

The anagrams of altars, stars, rats and tones.

And poems contain the imps of riddle and delight

As we find or impose our order through the night.

So thank you Zireaux for this verse by Crane

I'll stop my doggerel now 'fore joy turns pain.

And thanks for the kind words about Abandoned Car which have cheered and encouraged me to keep writing late into the night or in those early hours before work.

Post a Comment